The Arabic Alphabet: A Guided Tour

by Michael Beard

illustrated by Houman Mortazavi

B is for Bashibazouk

Not all letters have a proper name. In Arabic Ba is known simply by the sound it makes. Ba’. (In Persian it is Be, with a short e – just as, in English, B is just Bî.) The sound (like any sound) doesn’t mean anything. Ba starts as a shape, and when we pronounce it, it starts being useful. It did, however, once have a name.

Bayt, “house,” starts with Ba. And at one time Ba, in a way, started with Bayt. Some variant of bayt has meant “house,” dating back into pretty early writing systems. In Phoenician it was Bêt, in Nabatean Beth, in Syriac Bêṯ, in Hebrew Bet or Vet. In a way, that was the shape of the letter too. You can see a house, sort of, in the Nabatean Beth, or in Hebrew Bet, both modeled after the Phoenician letter, where three sides of a rectangle probably represent an enclosure opening to the left, a little box from which we could look out at the next letter.

It isn’t much of a house, but the shape of Arabic Ba retains even less a feeling of enclosure. If it’s a house, it’s open to the sky, the cross-section of a shallow bowl shape. It is a floating house without a roof: what gives it its identity is the dot which hangs below, a square with each side the length of the nib, hanging corner down. It is the shape of all the dots accompanying future letters, all of them necessary for identification.

Ba is also the model for the shape of the next two letters (the next three if we include the Persian letter Pa), distinguished from one another only by those dots (ت ث پ ب).

When a Ba begins a word (or Ta, or Tha, or Pa), or when it occurs after one of the six non-connecting letters, there is a rounded right-angle, a nice solid shape like the stern of a boat. When Ba occurs in the middle of a word (between two connectors), the boat or plate shape disappears and the dot hangs below a single notch. The notch is an upward stroke of the reed which barely interrupts the left-flowing line. If haste or carelessness strips it down to the minimal recognizable shape, or less, the notch may almost disappear. In those cases all you can do is scan for the dot below the line and hope you know the word in advance.

In its stand-alone form, written with a pencil or a ball-point pen, Ba is a saucer shape, with a steep rim. Shaped by a reed, it is not quite symmetrical. It respects the right-left motion of the moving hand and thickens along the bottom, rising on the left with a narrowing strip of ink, not quite parallel with the descending strip on the right.

Shaped symmetrically, common enough when written with a pen or pencil, it is still recognizable. Students are often taught it that way at first. It used to take that shape in the early days of computer script.

When All We Had Was ASCII

There is no particular reason to remember the American Standard Code for Information Interchange, but for a while in the early days of word processing it was all there was. ASCII, on a dot matrix printer, offered for each character a little rectangle, made up of 63 little dots, arranged seven across and nine from top to bottom. A selection of those dots were all we had to form each letter, so there wasn’t much room for a flourish.

I’m told that the ASCII universe had 95 characters: the 52 Roman letters (lower and upper case), ten numerals plus punctuation (evidently 33 items). None of the 95 looked much like an Arabic letter, but you could resort to a meta-alphabet to improvise what looked like recognizable Arabic. You couldn’t do it in one row. (Alif for instance was two backslashes, \ , one on top of the other. Dots below or above always require additional layers.)

The initial Ba (or Ta or Tha, or Pa) is one of the easiest shapes to form out of Roman letters. You just underscore a few spaces and add a right-parenthesis at the end (i.e., the beginning), plus a period on the line below…

__)

.

None of the three shapes took much ingenuity:

(_____) --\ _)

. . .

The stand-alone plate or bowl-shaped form is the most familiar. The two parentheses give you a symmetrical bowl. The word bayt, since the T and “ay” sounds share a shape with Ba, shows all three forms.

. .

(_____)--\_)

.. .

Big

Ba is for bozorg, Persian for “big,” büyük in Turkish — substantial things, things that last: a house for instance (thus the force of the curse yakhrab baytak, “may your house collapse”). Ba cities include the big ones: Baghdad, Baalbek, Bokhara, Babylon and Byblos (archaeological site of the earliest known alphabets, just north of present Beirut). Banâ’ is building, construction. In Persian a bonyâd is a foundation. A bâb is a door both in Arabic and in Persian. A bâb can be a simple wooden rectangle on the side of a hut, or it can be a substantial piece of architecture. Gates to a city, public buildings, mansions and courts, can be a sign of the institution’s magnificence. Our term Sublime Porte referred by metonymy to the Ottoman government, but it is an actual gate, a high one, called the Bâb-e ‘âli in Turkish & Persian.

Thus the poet Sa‘di’s great work the Rose Garden (Golestân) calls itself a garden with eight gates, each gate leading to a collection of anecdotes and poems on a particular theme. There is a bâb of the behavior of kings, a bâb of the morals of darvishes, a bâb describing the pleasures of satisfaction. It’s both a conceptual shape (a series of chapters), and a concrete image (garden with eight entrance gates). Calling your book a garden makes it a physical setting. You can wander there.

Solid

Substantiality, the massive, all that’s solid, is temporary. Towers can be proverbial for stability but also proverbial for the potential to fall. There are still substantial towers: some ziggurats, as of this writing, still exist in Iraq. The Arabic word burj (plural burûj), a tower, is said to come from Greek purgos, a Homeric term for towers and fortifications (e.g. Iliad 7.206). When the Qur'ân speaks of burûj, they are images of human vanity: “Death will find you out, even if you are in towers built strong and high” (Q 4.78). The same word elsewhere in the Qur'ân, as in the sûra entitled Burûj, calls on the other meaning of burj, the signs of the zodiac.

The Tower called Babel which we know from the Old Testament, in many accounts (though not in the Old Testament), famously collapsed. Those accounts, post-biblical, show the fragile side of a burj. In the Old Testament, Babil is the name of a city abandoned by its builders because they couldn’t understand one another. “Therefore is the name of it [the city] called Babel; because the Lord did there confound the language of all the earth: and from thence did the Lord scatter them abroad upon the face of all the earth” (Genesis 11.9).

Walls of Poetry

The word Bayt has two well established meanings combining the concrete and the non-material. Outside in the concrete world it is a house; in the realm of language, it is the fundamental unit of poetry. We could translate bayt by “line” or “verse,” but “couplet” might be closer, since the bayt is made from two parts of equal metrical length. What would it mean for a bayt of poetry to suffer that curse, yakhrab baytak, and fall apart? Perhaps it would mean for whole poems to break down into individual phrases and words cited out of context. It happens all the time.

Ibn Baṭṭûṭa

The Arabic stem B-L-D generates a verb “to be ignorant.” It is used in the Qur’ân with the meaning “to stay in one place.” In common speech the verbal noun, balad (accent on the first syllable), is the countryside. The adjective form, baladî (accent still on the first syllable), is used to describe someone rustic and perhaps a little slow. Balad can also be the word for kingdoms and countries, suitable for visiting.

Ibn Baṭṭûṭa (1304-1368), an Arab counterpart of Marco Polo (1254-1324), left behind him a famous account of his journeys. He grew up in an Amazigh (“Berber”) family in Tangier, at the western corner of the Islamic world. He started traveling east in 1325, at first projecting only a pilgrimage to Mecca, which would have been a considerable journey in itself, but then he just kept going, from one balad to another, and left an account of the trajectory (the Riḥla, or “Travels”) which could be good companion piece for Marco Polo's eastern journey from Venice a generation earlier. A compendium of Ba names could outline the itinerary. The first of the big cities was al-Qâhira, Cairo, whose central urban district was a Ba phrase, Bayn-al-qaṣrayn. Bayna is “between.” Bayn-al-Qaṣrayn is the district bounded by two tenth-century palaces (one palace, qaṣr, two of them, qaṣrayn), the Great Eastern Palace and the Lesser Western Palace, still a district of traditional Cairo. This is the Bayn-al Qaṣrayn of Naguib Mahfouz’s 1956 novel, the first of the Cairo trilogy (translated cleverly as Palace Walk).

If Cairo in the 1320s was among the most prosperous of Islamic cities, Baghdad was its contrary. It had been a particular target in the Mongol invasions of the previous century. (Another epic traveler, Robert Byron, would visit in 1933 and suggest that it still hadn't recovered: “The prime fact of Mesopotamian history is that in the thirteenth century Hulagu destroyed the irrigation system; and that from that day to this Mesopotamia has remained a land of mud deprived of mud's only possible advantage, vegetable fertility. It is a mud plain, so flat that a single heron, reposing on one leg beside some rare trickle of water in a ditch, looks as tall as a wireless aerial.”—46) You can’t help but wonder what he would see now.

Ibn Baṭṭûṭa seems to have been more interested to visit Basra, another Ba destination, which was still a major center of learning, downstream from Baghdad. Ibn Baṭṭûṭa spent a lot of time on the sea, in Arabic the baḥr the sea, even more time than on the biâbân, the Persian word for desert. (You can see the word âb in there, with the prefix bî, “without.”)

There is a Ba word to describe the antithesis of the city: badw (the noun form of badawî), that style of pastoral nomadism which provides the image in Islamic tradition of a pure and uncorrupted life, as pastoralism is regularly an image of positive values in the Old Testament (“The Lord is my shepherd” in Psalm 23). The word has wandered into English in plural form (with the suffix -în) as our word “bedouin.” Ibn Baṭṭûṭa from time to time would travel with Bedouins, for safety. A herdsman is a baqqâr, another Ba word, which is also the name in Arabic for the constellation we know as Boötes.

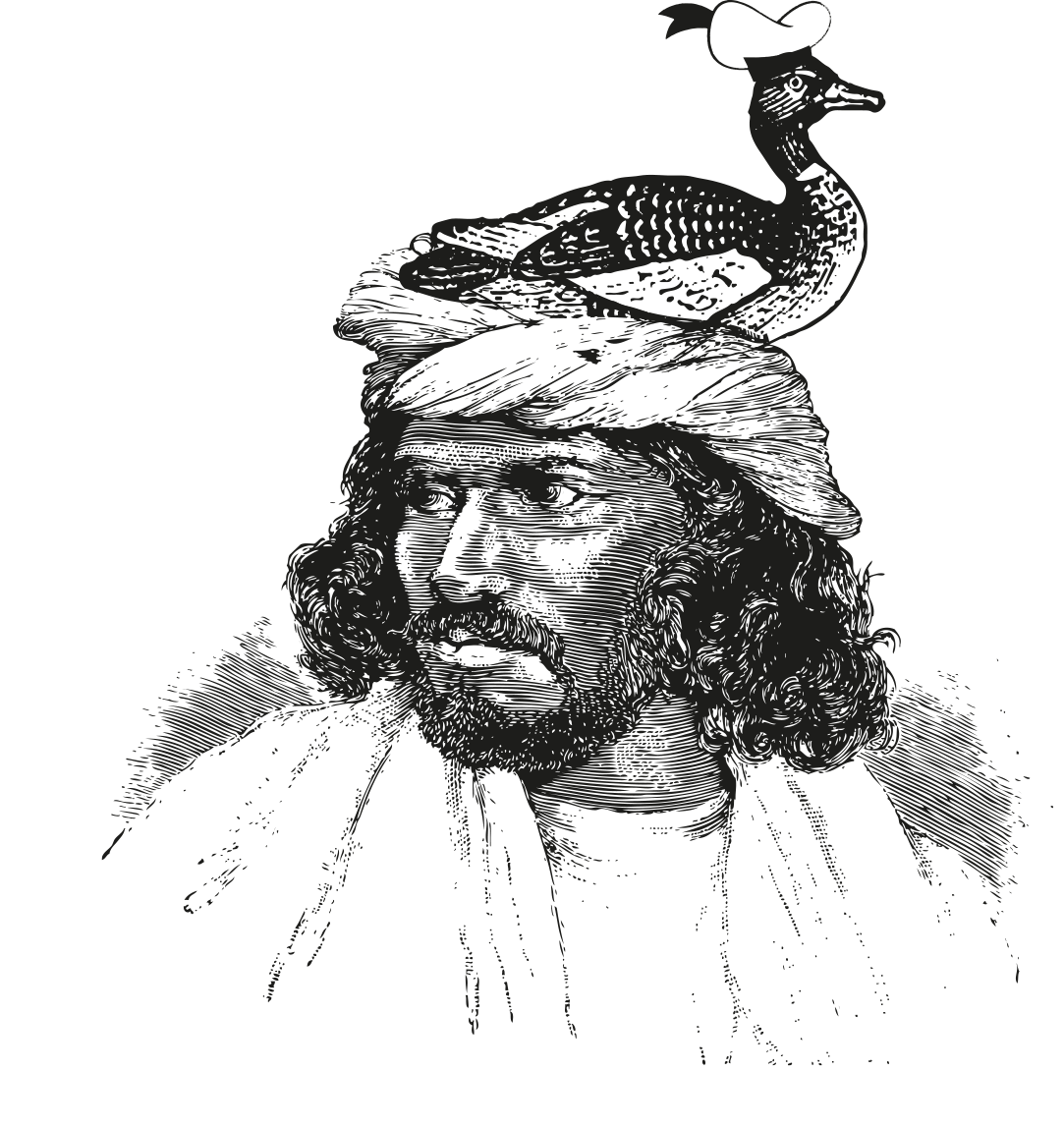

Baṭṭûṭ

Baṭṭûṭ is the name for Donald Duck in Arabic. (It comes from a diminutive for baṭṭ, “duck.”) Ibn Baṭṭûṭa’s name derives from the same stem. (No doubt there is a reason.) Both are travelers: Ibn Baṭṭuṭa out of curiosity. Baṭṭuṭ, in the comic books famously originated by Carl Barks in the 1940s, travels on junkets with his Uncle Scrooge, richest Duck in the world, to manage his far-flung investments. They show you familiar cartoon characters against exotic settings: exotic, over-simplified and, seen from the right angle, caricatures that we now associate with a demeaning portrayal of unfamiliar cultures.

Perhaps surprisingly, those same comics were once popular in the Arab world, translated into colloquial Egyptian Arabic. Dâr al-Halâl publishers in Cairo used to issue stories from the old familiar stock of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck narratives, from the classic age of American Disney comics (the Fifties and Sixties), in the children's magazine Miki, which appeared every Thursday in kiosks all over Cairo. The strip stretched from right to left, which means that the images needed to be reversed, so that multiple balloons in the same frame would scan across in the correct sequence. And then there’s the problem of proper names. Mickey Mouse is simply Miki. Daisy Duck is Zizi. And since the Disney comic-book characters often have names with meanings in English, the Egyptian translators found Arabic counterparts. Baṭṭuṭ for instance. Uncle Scrooge is ‘Amm Dhahab’ (“Uncle” plus a variant of the word for gold).

Mickey Mouse's sidekick Goofy becomes in Arabic a Ba name, Bandaq, the word for hazel-nut (Persian fandoq), “nut” having the same associations of mental dislocation in Arabic as in English. The name Goofy tells you what the possessor of the name is like, in the manner of Duessa in the Faerie Queene. Or Mr. Worldly-Wise Man in Pilgrim’s Progress.

Bandaq has more associations. Hobson-Jobson, Henry Yule’s great dictionary of Anglo-English colloquial speech (1903), deals with it under the spelling “bundook”:

The history of the word is very curious. Bunduk, pl. banâdik, was a name applied by the Arabs to filberts (as some allege) because they came from Venice (Banadik, comp. German Venedig). The name was transferred to the nut-like pellets shot from cross-bows, and thence the cross-bows or arblasts were called bunduk, elliptically for kaus al-b., “pellet-bow.” From cross-bows the name was transferred again to fire-arms… Al-Bandukâni, “the man of the pellet-bow,” was one of the names by which the Caliph Hârûn al-Rashîd was known, and Al Zahir Baybars al-Bandukdârî, the fourth Baharite Soldan (A.D. 1260-77) was so entitled because he had been slave to a Bandukdâr, or Master of Artillery. (Hobson-Jobson, 127-28)

Bandaq strictly speaking has nothing to do with Venice, but Banadik sounds like an Arabic plural, banâdiq. If Banadik, Venice, had been an Arabic plural, bandaq would have been its singular.

That plural form is common for Arabic stems with four consonants. A barzakh (a partition or isthmus) becomes in the plural barâzikh. A birqish (some kind of bird) becomes barâqish. Barbar (a “Berber”) becomes barâbira. Balshaf (a Bolshevik, pretty clearly a loan word) becomes balâshef. A bandar is a port; ports are banâdir. There is an Arabic four-consonant verb balbala, “to make anxious, to disturb.” One of the noun forms is bulbul. “Bulbul” could, I suppose be an indigenous Arabic word. The sound of the bulbul does, after all, disturb poets. More likely the noun “bulbul” drifted from Persian into Arabic and generated a set of Arabic phonological changes. Bulbul in Arabic does take a non-Persian plural, balâbil. A fair-minded philologist could see it either way.

Bulbul

The bulbul is not a large bird. In fact, though we usually translate it “nightingale,” it’s evidently not one bird at all. (The Encyclopaedia Britannica says “any of about 140 species of birds of the family Pycnonotidae, order passeriformes.” The OED says “thrush.”) Ornithologically speaking, as the word travels west its meanings scatter like a rooster tail. In poetic terms the nightingale is one species, the fundamental unit of poetic imagery, the center of lyric tradition. Read enough poetry with bulbuls in the foreground and it seems an emblem which defines poetry rather than a character in it. In English poetry it is traditionally a provider of background music for human actors, a bird that sings by night. In Persian poetry the bulbul is a personage in his own right. It embodies the obsessive predictability of lovers, pivoting around the rose (in a scenario of interspecies love) like a moth around a candle.

Bashibazouks

Baṭṭûṭ is not the only great cartoon traveler. We also have Tintin, drawn by the Belgian cartoonist Georges Prosper Rémy (1907-83) under the pen name Hergé. Hergé’s role during the occupation of Belgium (1940-44) was equivocal. He continued to work as a cartoonist for a journal under German control, and his reputation as an opportunist and collaborator has never quite left him. For many readers his cartoons have a spirit independent of the person, and they separate Hergé from his creation. It’s a separation not everyone can make.

He was an ambitious draftsman who tried out the Arabic script himself from time to time, sometimes as gibberish, sometimes, for some reason, in recognizable Arabic. His moments of accurate Arabic are evidence of some serious research, but the Eurocentrism is still easy to spot. His exotic scenes, the Middle Eastern settings for example, function as little more than a theatre for European visitors, but it’s a paradoxical Eurocentrism, since so many children read them are in the Middle East, in their own languages.

The cover of Land of Black Gold (published as a book in 1950) has the words al-dhahab al-aswad, “black gold,” inscribed under the title, recognizably in Arabic, right down to the diacritical marks showing vowels. Hergé obviously paid close attention to Arabic orthography, wherever he found it, enough to create the occasional Arabic poster or street sign in the background of a frame with an Arabic setting, and there are even speech balloons with Arabic conversation. He seems to have copied them from different sources, carefully but sometimes with little shifts of proportion that make them nearly illegible. Often his source is clearly a printed text, where he copied the fine space between connected letters which separates one letter from the next in typewritten Arabic.

Tintin’s sidekick Captain Haddock’s favorite insult is “bashibazooks,” which is in fact an actual Turkish term, a composite of bash, “head,” and bozuk, “broken.” Bash is one of those key words in Turkish (with a three-page entry in the Redhouse dictionary), foundation for one colloquial expression after another, among them a “broken head,” which became a term for the poor of Istanbul, who were coerced into military service as irregular forces. (The Redhouse dictionary gives for başıbozuk “civilian” and “irregular [soldier].”) The başıbozuks developed notoriety in Europe when they were trained for the Crimean War and later the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. Captain Haddock is not old enough to have encountered a başıbozuk in person. He means it as a general insult, a soft-edged one, usually directed against some cultural phenomenon he doesn't understand, which the recipients listen to with good-natured interest.

Bazaar

Başıbozuk made its way into English dictionaries (as “bashibazooks”) pretty much unchanged. The word “bazaar” has done the same, and spread further. The OED cites an occurrence of “bazaar” in English as early as the 14th century. Perhaps this is because the institution of the bâzâr was found throughout the Islamic world. It is one of those recurring vistas which tie the experience of one city to the next. In Persian bâ means “with” and zâr is one of the words for “gold.” It sounds like a sure thing that “with gold” is the etymology – it seemed that way to me — but evidently it goes back to a word in pre-Islamic Persian which has no gold in it. (In Arabic there is a word spelled the same way which means a person who plants seeds. No connection.) “Bazaar” is, like “agora” in Greek, a word with cultural connotations. (Its counterpart in Arabic, the word sûq, hasn’t traveled as far, but it means the same thing.)

The double A in English “bazaar” is a way of showing the distinctive long A sound of Persian. The English near-homonym “bizarre,” by the way, is also a borrowing, but unconnected. (“Bizarre” is from Basque.) The standard bazaar shape, a winding series of alleys, usually covered by a rounded mud-brick ceiling, with rows of open-front shops, is still visible all over the Middle East, in Khân al-Khalîlî in Cairo, for instance (the title of a 1946 novel of Naguib Mahfouz), or any of the urban centers in Iran, Afghanistan, and even in the Islamic neighborhoods in China. The great Persianist E.G. Browne says it well in his A Year Amongst the Persians (1893):

Bazaars… are much alike, not only in Persia, but throughout the Muhammadan [he means “Islamic”] world; there are the same more or less tortuous vaulted colonnades, thronged with horses, camels and men; the same cool recesses, in which are successively exhibited every kind of merchandise; the same subdued murmur and aroma of spices, which form a tout ensemble so irresistibly attractive, so continually fresh, yet so absolutely similar, whether seen in Constantinople or Kirmán, Ṭeherán or Tabriz. (103)

Entering the covered bazaar in Kerman, with its massive entryway and two-story opening corridor, used to evoke in me a feeling for which there is no equivalent in American life. (You certainly don’t feel it in a mega-mall.) It’s not quite like entering the intimate space of a private home, or a club, but it’s a protected communal space in which the time of day matters less, the outside seems less relevant, and the slowly-swirling dust clouds pass through the static shafts of light.

Aubergine

As fruit and vegetable words travel along the trade routes, the names are likely to change a little at every stop. In his entry under “brinjaul” in Hobson Jobson, Henry Yule identifies it as the eggplant, “the Solanum Melongena, very commonly cultivated on the shores of the Mediterranean as well as in India and the East generally.” The eggplant is popular all over the Middle East and the pronunciation changes eccentrically, from Persian bâdemjân to Arabic bâdinjân and baytinjân. Turkish patlıcan (the C pronounced like an English J), Urdu bhântâ, Portugese bringella, which Yule considers the immediate ancestor of Anglo-Indian “brinjaul.” (If we count emojis, the meaning can also change.)

There is a famous Turkish eggplant dish which contains another Ba term, imam bayιldi (bayιldı from bayιlmak, to faint). It is a name which translates literally as a complete sentence, “the imam fainted.” (Turkish folkloric tradition describes the village imam as a dinner guest with a voracious appetite.) French and British “aubergine” (the “au-” no doubt memorializing the Arabic definite article) forks off from the same stem.

When the Alphabet Migrates

Ibn Baṭṭuṭa remarks about China that it was one of the safest countries for travel. This was true of his physical self. The alphabet he used, on the other hand, ran into hard times. As he sails down the coast of the Bay of Bengal and then up the China Sea the place names become harder for him to transcribe. Some, like Tawâlasî, Qâqula and Kaylûkarî, located evidently along the south coast of Malaysia, still haven’t been identified.

The city since identified as Zhuang Zhou is transcribed Zaitun, the Arabic word for olive. (Zaitun would have been a sorry choice for a Chinese name. The Tang-period scholar Duan Sheng, in a book of oddities, listed the zaitun, transcribed zi-tun, as something exotic, a plant from Po-se — an early Chinese transcription of “Persia.” It was still listed as a rarity in an 18th-century Manchu dictionary. This comes from the research of the sinologist Berthold Laufer, in his Sino-Iranica.) Ibn Baṭṭûṭa identifies one city on the coast of Malaysia as Qâqula (now an obscure Persian word for Cardamom). He may or may not have gone to Khân Bâliq, today’s Beijing (the city Marco Polo, in a previous generation, had referred to as Cambalu). Khân Bâliq was easy to transcribe properly into Arabic letters because the rulers of the Yuan dynasty, descendants of Kubla Khan, were Muslims (with a holy book in Arabic script). Khân is Khan, as in Kubla Khan; Baliq seems to mean something like “city” in one language or another.

You can trace the eastern edge of Ibn Baṭṭûṭa's itinerary (1345-1346) by a series of stops along the coast which stretched from the bay of Bangla, skirting today’s Bangladesh through the Straits of Malacca, to the China Sea where he found Hang-Chou, capital of the Southern Sung dynasty, the biggest city he had ever seen. With satisfying narrative symmetry, he meets at his furthest point from home, in a city he calls Qan, an Arab from a Moroccan family, a scholar with another Ba name, al-Bushrî. Much later, at home in Morocco, he meets the same scholar's brother, which Ross Dunn (in his study of Ibn Battuta’s travels) quotes as a supreme example of irony in the Riḥla: “How far apart [ba‘îd] they are” (296). Irony and understatement.

Hoodies

Words whose itinerary takes them back and forth across the Mediterranean are easier to trace: the Greek word birros means a Christian clerical garment (presumably a monk's cowl) which becomes in Arabic the item of clothing called a burnus, in English “burnoose.” (A burnus, plural barânis, is the hooded robe we expect to see in North African bazaars, full-length hoodies. Jedi knights wear them.) As the trail of cognates travels back to Europe, for some reason it develops into the opposite of a hooded coat, Italian beretto, English biretta, a little square hat which has an official and non-practical look (a miniature hood without the cloak?). In French it went through the same process of miniaturization and became the word beret. For some reason, when the same word arrives in English as “burnoose,” it means the same thing as Arabic burnus.

Words Which Go Downhill

Sometimes a word entering English takes a downward semantic turn, the direction of umm in Turkish. Sometimes you feel you can imagine scenes where the change must have taken place, the moment the language learner refuses to hear a word’s proper meaning and gives it its insulting spin.

Bakhshidan is simply the infinitive form of a polite Persian verb for giving, bestowing and forgiving. The imperative bebakhshid is in Persian the standard way to say “excuse me.” The verbal noun bakhshish is the form we are likely to run into it, which English speakers recognize as a term for unearned largesse, a tip or a bribe. Yule, spelling it “bucksheesh or buxees,” translates as “buona mano, Trinkgeld, pourboire,” adding “we don't seem to have in England any exact equivalent for the word, though the thing is so general.” We don’t really need an English equivalent. Bakhshish is familiar enough in English to fill the blank for us, even though in Persian the same word simply describes gifts, neutrally. (The Persian word for English bakshish is reshveh, a borrowing from Arabic rishwa, which, after that single borrowing, has never left home.)

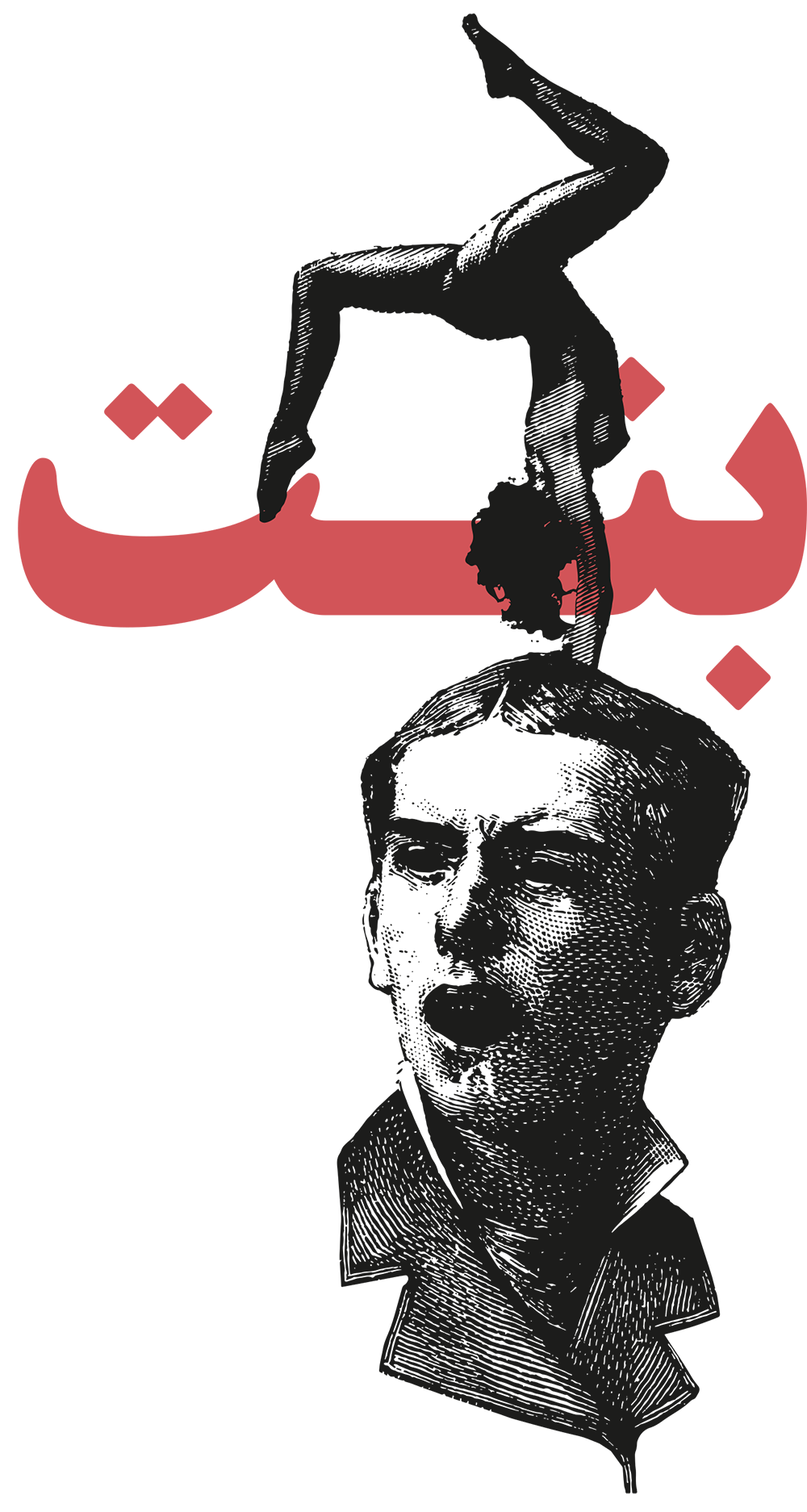

Bint is an innocent word in Arabic, feminine counterpart of ibn, son, with a feminine suffix -t. Thus “daughter.” You hear it as a plural, banât, in Banât al-na‘sh al-asghar, the three stars of Ursa Minor which, if we see it as a dipper, make up the handle. (The tip of the handle is the North Star. A dependable, unbudgeable bint. If the bowl is the coffin, you wonder who’s inside. It’s right at the center of the sky. There must be a story there.)

Starting from neutral “daughter,” bint has become the word for a prostitute. This is the only meaning that survived when it showed up in English. You hear the English word “bint” in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) when the peasant interrogates King Arthur on the origin of his authority. (We’re likely to know the story: the Lady of the Lake presents Arthur with the sword Excalibur.) The peasant’s argument is in two parts: “you can’t expect to wield supreme executive power just because some watery tart threw a sword at you.” Then he repeats it in Orientalist terms, making Excalibur a scimitar: “I mean, if I went round saying I was an emperor because some moistened bint had lobbed a scimitar at me, people would put me away.”) As the comparatist Wlad Godzich explains in an article about that film, revealing how the scene looks to a medievalist film-goer, there is a series of coded references going on. Here we have two of them: if the sword is a scimitar, i.e. an artifact of the east, the woman is logically a bint, innocent in Arabic, in English, an insult. The whole history of the empire and its ability to reduce individuals to demeaning social roles is there, foreshortened.

BARF

There is a passage in Rumi’s Masnavi, towards the end of Book Four, which demonstrates the great distances between the human world and the world beyond it. It turns out that Mount Qâf, the mountain that surrounds the earth, can talk. Dhu’l-Qarnayn (probably the folkloric version of Alexander — it doesn’t matter) reaches the boundary of the earth and asks the mountain to tell him what the universe is like beyond the one we know. Mount Qâf replies that it’s beyond our comprehension. The barrier between us and it (which is, presumably, Mount Qâf himself) presents snowy mountain after snowy mountain. Everlasting snow accumulates.

Kuh-e barfi mi-zanad bar digarî

Mi-resânad barf sardi tâ tharî.

Kuh-e barfi mi-zanad bar kuh-e barf

dam be-dam z-anbâr-e bi ḥadd shagarf.

One mountain joins the next one that is found

and snow brings frosty coldness to the ground.

More snowy mountains stretching out for miles;

Each moment from the storehouse come more piles.

The description of that endless, inhuman and sublime barrier lasts for seven bayts, and the word “snow” occurs eight times. It's very beautiful. (And by the way there's a passage uncannily like it in Alexander Pope’s “Essay on Criticism.”)

The word “snow” in Persian, Rumi’s leitmotif in an overpowering spiritual vision, reads oddly when an English speaker is faced with the original. The word for snow is barf, a delicate and charming word in Persian, for a substance which descends silently from above. In English “barf” is less delicate. When we learn that Tintin’s dog Milou, “Snowy” in English, is “Barf” in Persian, it sounds off somehow.

English “barf” and Persian barf came into a public collision in the late 1960s, on every shelf where household goods were sold, when an Iranian brand of powdered dish soap named barf appeared on the market, in a box with the Persian name transliterated in English letters, plus a motto which said how bright you could get your clothes, with Barf. Can you blame me for wanting to bring a box of it to the U.S.? Unhappily, by the time it occurred to me to buy one, so I could take it back to share with linguistically minded American friends, the English logo had been changed. The transliterated brand name printed on the box had been replaced, and all the English letters said was “Snow.” Sharing the soap named “Barf,” sure-fire humor, was now an idle dream.