The Arabic Alphabet: A Guided Tour

by Michael Beard

illustrated by Houman Mortazavi

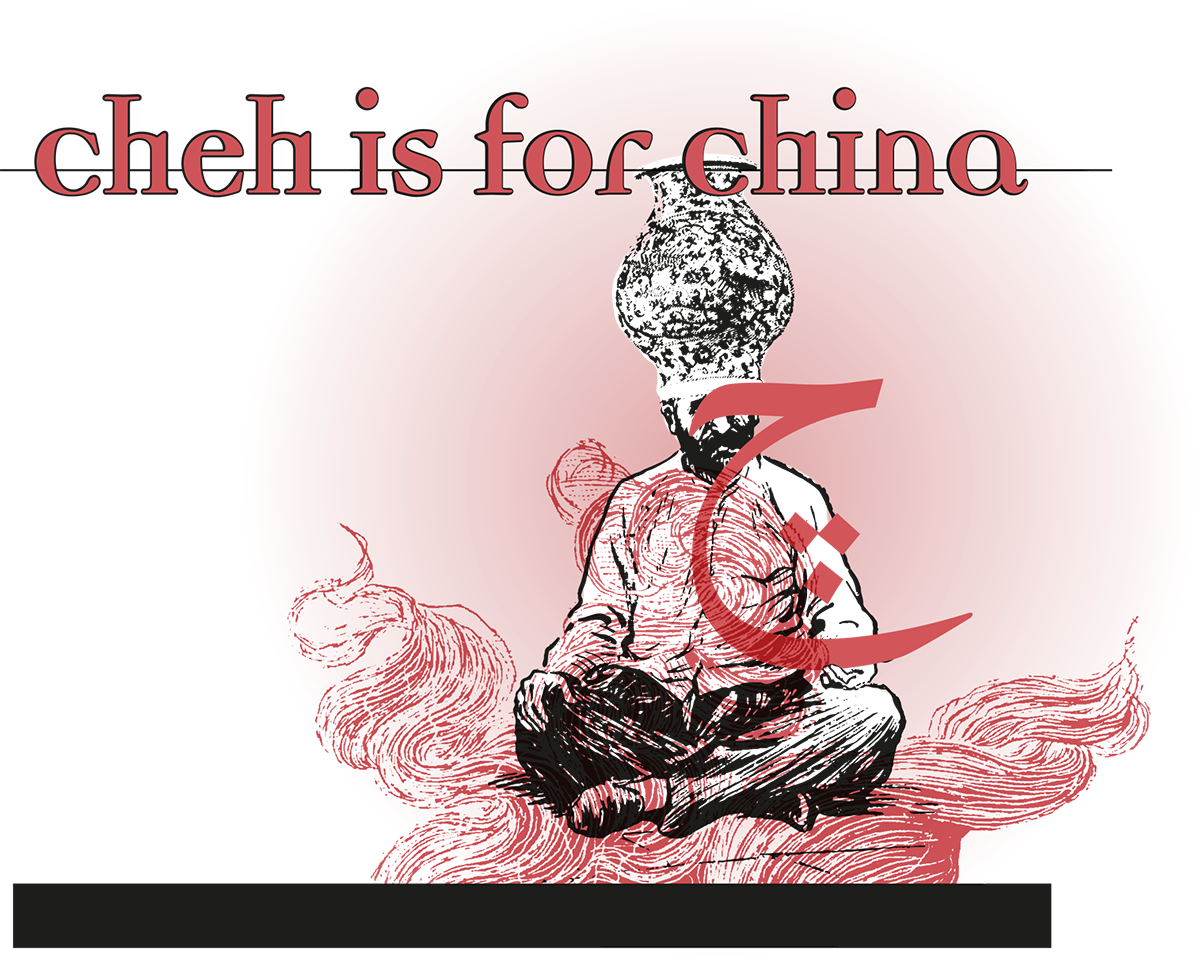

Cheh is for China

Let’s say we’re reading Ferdowsi’s culture-shaping Persian epic, the Shâhnâmeh, and we run into names like Manouchehr or Bahram Chubin, heroes who are châlâk (“agile”), perhaps châreh-gar (“resourceful”) or chireh (“victorious”). Or who rise to meet a challenge (châlesh). We have at hand a vocabulary of epic heroism, with a letter you will not find in the Arab world, where the sound CH does not exist. An alphabet without CH would be incomplete in Persian, Turkish and Urdu as well. (I’m oversimplifying. In Urdu, where the same letter is called Chim, on analogy with Arabic Jim, it represents two separate CH sounds. Long story). The sound exists, I am told, in Iraqi dialect (but not represented by Cheh).

At one time, evidently, it was a problematic sound in English orthography too. After all, we need two letters to render it, which tells us something. The French need three (tch), or sometimes four (tsch). The two letters of English CH create some awkward moments too. How do you double it? How do we transcribe in English the Persian word for “child,” which sounds something like “batch-che”? In Persian we would write the word with three letters: Ba, Cheh and an “eh” sound (shown by the letter H — there are reasons). The Arabic and Persian alphabets don’t show double letters by writing them twice (there’s a diacritical mark available for it if you like, something like a little rounded W), so the word in Persian is three letters; بچه But if you’re going to be precise in English, what can you write but the barely readable bachcheh, with a double CH? We use up a lot of letters (eight versus the Persian three). And even in transcription it’s not immediately obvious how to pronounce bachcheh. In Italian, where a single-letter CH-sound exists, it would be easier: baccè (with the double C of accento or accidente).

There are the epic Cheh words familiar to readers of Ferdowsi, but domestic and homely ones are probably more common. A chupân is a shepherd. (It’s the origin of Choban, the brand of yoghurt, from Turkish çoban.) A chupuq is a pipe. A chakosh is a hammer. A châqu is a small knife. Charb is grease. Chap is “left,” as in “left hand” or “leftist.” A chatr is an umbrella. A châh is a well. Châh-dalv is Aquarius. (A dalv, Arabic dalw, is a bucket.) Cheshm means “eye,” and with a suffix -eh, it becomes cheshmeh, a spring or source. (For some reason the Arabic word for eye, ‘ayn, also doubles as the word for a spring or source — without a suffix.) A chahâr-pâ is a quadruped, since chahâr is Persian for the number four, and pâ is a foot. (The more scientific equivalent is charandeh, grazing animals, from the verb charidan, to graze.) Grazing takes place in a chamanzâr, a meadow.

There is a town by the name of Chaman in the north of Afghanistan, on the border with Pakistan. (The border is porous, and this has become a source of trouble in the Afghanistan conflict.) At the time of this writing, it would not have much appeal for a tourist. But years ago, in very different times, an Italian friend fluent in Persian observed that he would have liked to have one of those signs on his car that suggests an itinerary. (Like Akron/Haight-Ashbury, Paris/Tibet, or in the 1850s “Pike’s Peak or bust.”) The sign he suggested would read Prato (in Tuscany) on the left and Chaman on the right. Prato means chaman. Both names mean a meadow or a field. So the epic car trip would take on a circular quality.

A châdor is a tent. I’m told that in Bengali chader means “cloth.” In Iran a chador is also a particular kind of veil — a semicircle of cloth, worn wrapped around the body, including the head, like a very long coat with a hood, with the face open. One holds it with the hand at the neck, to be tightened or loosened depending who is nearby. Black is the color for the more conservative. There is a style in white cotton (for prayer, a chador-namâz, namâz being “prayer”). The style I’ve seen most in Iran is made of Cheh word chit (pronounced “cheat”), chintz with a floral pattern. (A variant, châderi, is the word used to describe a burqu‘, English burka, that much more restrictive veil worn in Afghanistan, something like a portable prison with a cover over the face which looks like a fencer’s mask.)

A chughundar is a beet, homely vegetable made more homely still because, I am told, it used to be an insulting term to describe a woman wrapped in a châdor.

In contemporary Turkish orthography, the J sound of the letter Jim is represented by the letter C. To make it an unvoiced sound, English CH, one simply adds a little stroke underneath called a çengel, something like a French cedilla: ç. Thus çehre is for face, çesme for spring, çoban for shepherd, çubuq for “pipe,” çügündur (or çukundur) for chughundar. The name changes. The thing remains.

Thing

Chiz, the word for “thing” in Persian, a homonym of English “cheese,” a cognate of French chose, is not strictly speaking a question word, but it is by nature vague and undefined. It doesn’t specify what the thing is. And so you may hear “cheh chizi …” “what thing …” as in “cheh chizi barâye pâk kardan-e lakkeh-ye morakkab-e Chin khub ast,” “what [what thing] should I use to erase an ink stain?” As one says in Italian che cosa (“what thing?”) or in modern Greek ti pragma?

In Persian CH we have something like wh- in English, the opening of all those question words like “why,” “who” and “where.” (It’s the counterpart of qu- in Latin — Quis? Quid, Quantus? or in French, pronounced differently — Qui? Quand? Quoi? Quel heure est-il?) Cheh plays that role in Persian. Alone it means “what.” Che-ṭowr (“by what means, in what manner”) is “how.” “Ḥâl-e shomâ che-ṭowr ast,” “How are you?” is one of the standard greetings. Chand is “how many.” Che qadr is “how much.” Cherâ is “why,” which (according to some logic I can almost sense but not quite) also means “yes.” (Why not?) Chun is “since,” “as,” “because,” and a chun-o cherâ, a “because and why,” is an argument. Cheh plus -ast (“is”) makes chist. Add ân, “that,” or chist ân – “what is it that … ?” A chistân, a “what is that,” is a noun meaning a riddle. (For instance, this kind of question: what is it that everywhere, but no one sees it? Air. Havâ. What is it that has two feet and borrows two more, but wherever it goes you can’t keep up with it? A bicycle, a dow-charkheh.

Lamp

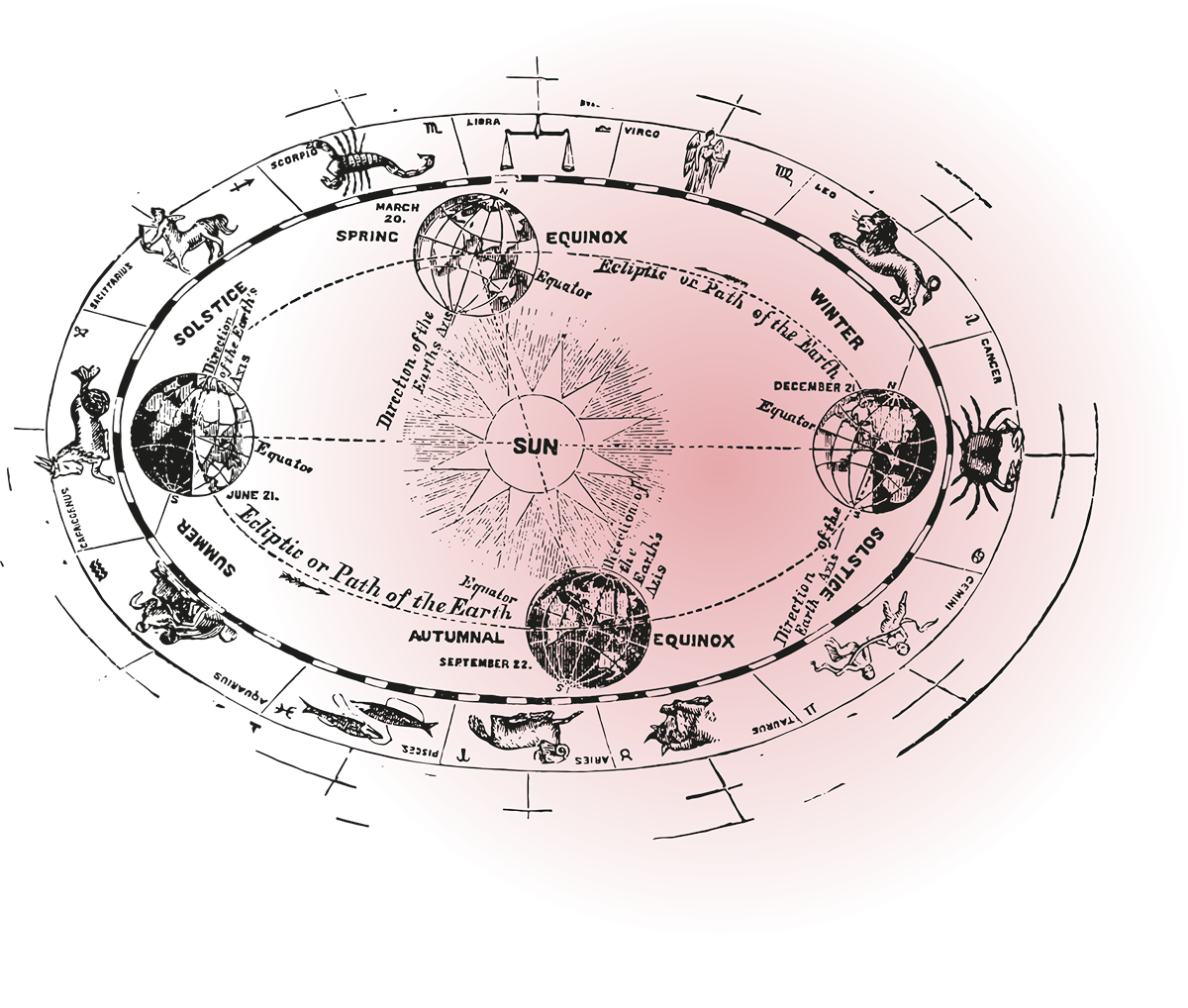

Charkh, a wheel, commonplace enough, has a secondary meaning which takes us beyond the world of household objects. The sky, because it turns, is often simply “the wheel.” It is often expanded to charkh-e falak, the wheel of the sky. In one of ‘Umar Khayyâm’s quatrains (FitzGerald paraphrased it), the night sky is reduced to just one more household object, the children’s toy we know as a magic lantern:

In charkh-e falak ke mâ dar u Ḥayrân-im

Fânus-e khiyâl az u mathâli dânim:

Khurshid cherâgh dân-o ‘âlem fânus—

Mâ chun ṣovar-im k’andar-e u gardânim.

[This celestial wheel (charkh-e falak) inside which we stand, amazed-- / let’s look at it as a magic lantern: / The sun is the candle (literally a lamp -- cherâgh); the world, the lamp shade (fânus) which encloses it, / and we, like shadowy forms, circle around inside. (Actually I thought of cherâgh and fânus as synonyms, but I stand corrected.)

This great carousel on which we ride

Has the rotating lantern for its model.

The sun is the lamp, the world its outer shade,

And we are the images on it, aimlessly floating by.

—trans. Karim Emami]

Astronomy was among Khayyam’s skills, though you wouldn’t guess it from this quatrain. We don’t learn any science from it. Perhaps the opposite. We do learn something though, and it’s a little surprising, at least to me, that there was such a thing as a magic lantern already in the 12th century, and it was familiar enough to use as a simile. According to this comparison, the sky is just another children’s game. The celestial charkh is just the lamp shade (in FitzGerald’s paraphrase, “a sun-illumined lantern”) with the constellation shapes pin-holed on it. What’s inside, playing the role of sun, is a cherâgh.

Cherâgh, lamp, can be a word with a mystique, perhaps because its Arabic equivalent (miṣbâh) figures as a mysterious, mystical object in the Sura called “Light” (Surat al-Nûr 24.35). Often too it is just a lamp. In 1979 I was carrying on a correspondence with an Iranian friend in Tehran, who was watching the events of their revolution spiral around him and thinking about history. He had a long memory, and he was in his seventies: he had seen the last Qajar monarch, Ahmad Shah, after that the twenty-year reign of Reza Shah, and he had seen the years of Reza Shah’s son Mohammad. He had seen donkey carts crowding the streets; he had seen the gradual accumulation of cars which, generation after generation, persisted in clogging the streets of Tehran, and now he watched airplanes overhead. He wrote with a kind of melancholy about the way history kept disappointing the Iranian observer, and summed it up with a verse proverb, a bayt which has haunted me ever since, with another Cheh question word and another cherâgh:

Fereshteh-î keh vakîl ast az khazâ’en-e bâd

Che gham khorad ke navazad cherâgh-e biveh-zani?

[The angel in charge of the storehouses where the winds are kept: / What sorrow (che gham) does he feel if the widow’s cherâgh blows out?]

First you look down at the earth from above: a mortal reader gets a chance for a brief moment to see the world from the point of view of an angel with an important job. We identify with the big forces. Then we see the same forces from underneath, moving from the big powers to take in the scene from the point of view of their victims. The reader may even feel a little guilty at having identified with that angel. Sometimes, perhaps always, history is like a hurricane, blowing out the lamps of powerless people. It’s knowledge you can find without looking very far.

China

“Utlûb al-‘ilm, wa law bi al-Ṣîn,” “seek knowledge (al-‘ilm), even in China”: the Arabic proverb is a Ḥadîth, a saying attributed to the Prophet. Ṣîn means Persian Chîn, the word for China. Chîn stems from the name of the Chin Dynasty (255-204 BCE). (Arabic Ṣin is another variation.) The intermediary is Sanskrit. The Ḥadîth recommending China as a place to seek knowledge generates the narrative of ‘Attâr’s 13th-century allegory Manṭiq al-Ṭayr, the conference of the birds. A flock of birds goes on a mission seeking the ultimate bird, the Simorgh, whose spiritual power extends right out to the feathers:

Dar miân-e Chin fetâd az vei pari

[In the middle of China one of his feathers fell …]

Har kasi naqshi az ân par bar gereft;

Har keh did ân naqsh kâri dar gereft.

[Everyone had an image of it. / Everyone who saw those pictures imagined it in his own way. –Manṭaq al-ṭayr, 47]

The mystical bird which lets a feather drop is like the Lord giving a revelation to mankind. To mankind has been granted the Qur’ân; the people of China are granted a feather, but a feather of mystical power. It’s a simple formula: bird, feather, and the people who find it: divinity, holy book, believers. The foreshortening of human history makes the listener feel outside human time. And once that bird called the Simorgh has shed that feather, people in China and in the rest of the world can talk of nothing else:

آن پراکنون در نگارستان چین است

.ا«اطلوب العللم و لو باللصین» آز این است

Ân par aknûn dar nagârestân-e Chin ast:

“Utlûb al-‘ilm wa law bi al-Sîn” az in-ast.

[That feather now is in the picture gallery of China; / And that’s the reason for the phrase Utlûb al-`ilm wa law bi al-Ṣin.]

Chin in Persian isn’t the only Chinese word that went abroad. There is a word chá in Chinese (茶, second tone), which has entered Persian, retaining the hard CH consonant, as châi. Châ’î is a word still heard in British slang, attested as early as the 16th century. (I checked.) In an alternative form, shâ’î, it enters Arabic dictionaries too, recognizably the same word transposed into a language without the harder sound of Che. Chá is also the source of our word “tea.”

When E.G. Browne approached Tehran in November, 1887, his party stopped at a road-side tea-house, adding that it would be his last for a while:

Many such tea-houses formerly existed in the capital but most of them were closed some time ago by order of the Sháh. The reason commonly alleged for this proceeding is that they were supposed to encourage extravagance and idleness, or, as I have also heard, said, evils of a more serious kind. (89)

Tea houses were reinstated in the 20th century, as travelers can attest. It seems hard to imagine Iran without them.

$

A transplant from China which took longer to establish itself abroad was Cheh word chav or chao, from Chinese chāo (1st tone). (The character for chao, 钞, consists of the radical for “gold” on the left and the character for “little” on the right.) The word chāo took an interesting turn in the 13th century.

Hulagu (or Hülegü), great grandson of Genghis Khan (in Persian Cheh name Changiz), after destroying Baghdad (656/1258), defined the western boundary of his empire (or rather had the western boundary defined for him), thanks to a famous defeat at the hands of Egyptian Mamluks at ‘Ayn Jalut in Palestine. He went east and set up the Ilkhanate dynasty, with a capital in Tabriz, extending from the areas we now call Iraq to modern Pakistan. His grandson Gaykhâtu ruled for only four years (1291-1295), and during that short reign is said to have spent cash with wild abandon. In 1294, with the help of his prime minister Sadr-e Jahân, his administration experimented with the Chinese system of creating money on paper with block printing. Apparently, with the help of the ambassador from China, where Kubla Khan reigned, Sadr-e Jahân designed chāo (钞) on the Chinese model, including inscriptions in Chinese. In E.G. Browne’s description,

The notes consisted of oblong rectangular pieces of paper inscribed with some words in Chinese, over which stood… “There is no god but God, Muhammad is the Apostle of God,” in Arabic. Lower down was the scribe’s or designer’s name, and the value of the note (which varied from half a dirham to ten dínárs) inscribed in a circle. A further inscription ran as follows: “The King of the world issued this auspicious chao in the year A.H. 693… Anyone altering or defacing the same shall be put to death, together with his wife and children, and his property shall be forfeited to the exchequer.” (Browne, Literary History 3.37-38)

Browne adds that, with the currency, proclamations were sent to all the major cities under Gaykhâtu’s administration, answering imagined objections to the new currency, and appending a couplet in Persian:

Châv agar dar jahân ravân gardad -- Rownaq-e malek jâvdân garded.

[If in the world this chao (châv) gains currency,/ Immortal shall the Empire’s glory be. --Browne’s translation, Literary History, 3.38]

The word châv (or châw), i.e. châp, can still be found in Turkish or Persian dictionaries, if they’re big enough. Gaykhâtu issued them, but the public’s refusal to use them was universal. They never became current (ravân), and he was obliged to withdraw them. Gaykâskhtu did not become jâvdân, “immortal,” except in the sense you can still find his name in the books of specialists and dilettantes. The conditional in the couplet (agar— the chao catches on) seems in retrospect the key word.

Since then a tradition of paper currency has become perfectly respectable both in Europe and in the world where the Arabic script dominates, but it took a while. (In the Ottoman empire it began in 1840, under Abdulmecit. In Iran, paper currency begins in 1890, under Shah Nasir al-Din.) Today the term for it in Persian is a loan word, eskenâs, which traces back to the French term assignat, the paper money issued in revolutionary France in the 1790s.

You will find a few words in Arabic script on the back side of Chinese paper currency, among five scripts which represent the five major peoples. (Actually they could have included a lot more than five.) The first, written at the upper right in Roman letters (what in Chinese is called pīn yīn), says, in Chinese, Zhōng-guó rénmín yínháng, “The People’s Bank of China.” Zhōng-guó is China; rénmín is “people,” as in rénmínbì, RMB, the Chinese currency; yínháng is “bank.”) Anyone who knows the Roman script could sound out the letters. The other four, in two rows underneath, are more of a challenge. They represent four more peoples, the same four represented by the small stars on the Chinese flag. The top row is, on the left, Mongolian, on the right, Tibetan. The second on the lower row is Zhuàng, the largest minority, from Guangxi in the south (written in pīn yīn).

The lower left language is the language of Uighurs in the west of China. Its appearance on the money is one piece of evidence among others that the central Chinese like to keep the Uighurs close. The language, a variant of Turkish, is written in Arabic script:

جۇڭگو خە لق بانكسىى

...jung-gow khalq bankesi.

The Uighur words in Arabic script are first the denomination, then three loan words: 1) Jung-gow transcribes the Chinese word Zhōng-guó, the middle country, i.e. China. 2) Khalq, from the Arabic khalaqa, “to create” is an Arabic noun meaning “creation,” i.e. “people.” (In Chinese it would have been rén-mín.) In this case it’s the bank of the khalq, the people’s bank. 3) As for “bank,” it’s just the English word “bank,” one of those loan words which shows up regularly in European and Middle Eastern language. 4) The Uighur suffix -esi in bankesi, is the first indigenous element, a kind of possessive (“its bank”) which plays a role common in numerous Turkish dialects. Zhōng-guó khalq bankesi. Six syllables, four major language groups. Chinese, Arabic, English, and a Turkic suffix.

Two Kinds of Printing

The contemporary Persian word châp, “printing” (pronounced like English “chop”) sounds as if it too might be a loan word from Chinese. After all, when you visit China you find that the molds used in block-printing are referred to in English as “chops.” “Chop” turns out to be a loan-word in Chinese as well, evidently from Hindi, where chhap means “imprint, stamp, publication.” Whatever the origin of the word, some kind of printing comes twice to Iran — once from China in Gaykhâtu’s day and then definitively, in the 19th century, from the other direction, the kind with movable type.

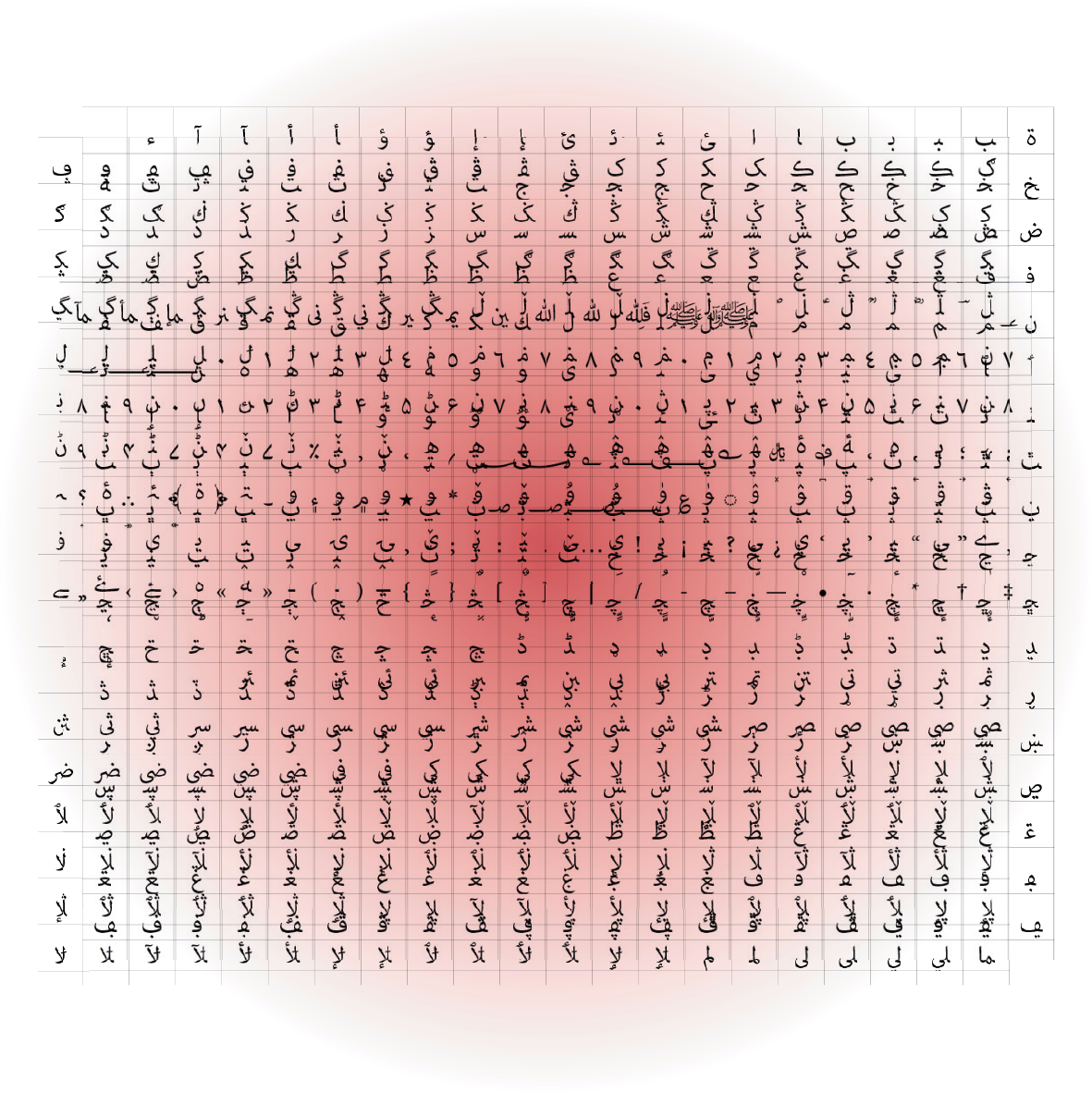

Chidan is the verb in Persian for picking (e.g. flowers), collecting, arranging, setting a table. One form of the verb (its root) is chin (homonym of Chin, “China”). Ḥoruf-chini is typesetting. (Ḥoruf are letters. You pluck letters out of the case.) In English the word “setting” emphasizes the act of putting the letters into the composing stick. In Persian the emphasis is a step earlier in the process, on the act of choosing the letters out of their case. The difference is probably arbitrary, but it makes sense. The pieces of print to choose from make Ḥoruf-chini a bit more elaborate. You need more pieces of type than you do with the Roman alphabet. It can be a lot more: “A complete font, including vowel marks for recording the Koran and other vocalized texts, runs to more than six hundred, plus huge quantities of leads and quadrats [the pieces of a font which are blank] to be placed between vowel marks and lines” (Sheila Blair, Arabic Calligraphy, 487). It’s just as well she doesn’t itemize, and it’s clear that most presses didn’t have a full set of 600. She adds, “The 24-point Arabic font developed for the French Imprimerie Nationale in the nineteenth century filled four cases and contained 710 different sorts” (ibid). And yet it was possible somehow to accommodate all the letters and their variations. (It was certainly easier than Chinese, whose early presses are said to have had an arsenal of 60,000 characters.)

The typewriter eliminates the need for a Ḥoruf-chin. Its letters are already there in front of you. The typewriter which generates Arabic script encounters some extra difficulties, not just because the cylinder moves the other way, but because the number of necessary character shapes is considerably greater – not 710, but enough to require some ingenuity. There’s a story about how the ingenuity came to be. It has to do with two inventors — Selim Hadadd (Syrian) and Philippe Waked (Lebanese-Egyptian) — working separately, both of whom applied for a patent in 1899. (There’s a full account on a Kerning Cultures podcast.) The problem an Arabic keyboard has to overcome has to do not with the number of letters (28 or 32), but with another complication. On the familiar western keyboard you have only two forms for each Roman letter — uppercase and lowercase. All you have to do is press the shift key and get from one to the other. Capitals aren’t an issue for Arabic, but for most Arabic letters you do have those three forms: initial, medial or terminal. What you need is a system where two settings can show all three. The first step is to invent a keyboard where you press the “shift” key and get the terminal or stand-alone form. The complicated part is to design a font in which both the initial and medial forms are both recognizable and identical. That is, each letter will have to be able to start a word or to connect on both sides. For one thing, you need to design them on a single base line, so when the letters need to connect they will line up against one another, usually with a tiny space between.

The three Arabic letters with the Jim shape, for instance, have the pointed side right at the edge, at the same height where the preceding letter will touch there (or almost). The lower arc of the letter needs to curve down slightly and then rise just to that level, to connect to the next letter. At that same height. The three are lined up together at the upper right of the keyboard, where O, P and “[“ are located on the Roman QWERTY equivalent. On a Persian keyboard you would find Cheh on the upper right, next to the other three, tucked into the corner like an afterthought.