The Arabic Alphabet: A Guided Tour

by Michael Beard

illustrated by Houman Mortazavi

Tha is for Soraya

Add a third dot to Ta and we have Tha, the last in the series of plate-shaped letters. Among the commonly taught languages the Tha sound (the unvoiced th- of “thin,” "path,” “thud” or “both”) is rare, but standard Arabic shares it with us (and with Greek). In English we use a single pair of letters (T plus H) to represent both Tha and its voiced equivalent (the th- of “this,” “the” or “either”). Standard Arabic has both of the TH sounds in its arsenal, with separate letters for each one. (The voiced sound comes along four or five letters further on.) There was a time when English too had separate letters for TH and TH (one called “thorn,” þ, and one called “eth,” ð), but reading English now, of course, if we want to distinguish them we’re on our own.

Ahmad Amin’s Qâmûs al-‘âdât wa al-taqâlîd wa al-ta‘âbîr al-misriyya (Dictionary of Egyptian customs, traditions and expressions —Cairo, 1953), a personal anthology, full of individual reminiscences and oddities, arranged in alphabetical order, admits to a gap in the data. Under the rubric of Tha there are no entries whatever, just a brief note of two sentences explaining that the letter Tha is not pronounced in Egyptian dialect: but that it bifurcates into two more familiar sounds, usually a T (thus thaqîl becomes taqîl or, more accurately, ta’îl — long story) but sometimes into an S sound, so that thawâb, a good deed, becomes a sawâb, in Persian a savâb. (In Persian too the letter Tha exists, but the sound — once a phoneme in Avestan, pre-Islamic Persian — has not survived. Today Tha in Persian is simply pronounced S, referred to as Se seh-noqteh, “the S-sound with three dots.”) Since Tha words are peculiarly Arabic, Tha in a Persian, Turkish or Urdu text will be the unerring sign of a borrowed word.

Tha descends from the same Nabatean letter as Ta. In Arabic it’s the extra dot that makes the difference. The three cluster in a triangle, like a stack of cannonballs or oranges. (Tha is for thamar, “fruit.”) In handwriting the three dots can become (as with Pa) a little circle.

Three

Tha is also for thalâtha, “three.” Thâlûth is the Christian notion of the trinity. Thulûth is the word for a fundamental style of cursive script which developed in the 11th century, whose proportions were developed by the tenth-century calligrapher Ibn Muqla. The threeness of the script must mean something. I don’t know it. (Yasin Hamid Safadi, in his always useful Islamic Calligraphy, cites two common explanations, neither very satisfying.)

There are three Tha animals which show up regularly in folklore and literature. First, Tha is for tha‘lab, a fox. Foxes are not linked with hen-houses, as they are in English, and there are occasions where they are not wily. In a famous parable (from the great story collection Kalila wa Dimna) a fox attacks a drum hanging from a tree, blowing in the wind, and is disappointed that there is no meat inside. The great 8th-9th-century essayist Al-Jâḥiẓ says (in “The Book of Animals”), not so much that the fox isn’t wily, but that the dog is more cunning. In the case of Tha animal tha‘bân, “snake,” cunning is not an issue. Snakes can be negative. (The villain Zahhak in pre-Islamic Iranian myth has snakes growing on his shoulders. They eat human brains.) They can be positive. (The hair of the beloved in romantic poetry — mâr-e sar-e zolfat-e tow — can be compared to a snake simply because it’s curled.) Or they can be valued for their antiquity.

There are commentators who see in Al-Jâḥiẓ’s writing a precursor of the concept of evolution. Fish, for instance, were originally snakes. The ones who became fish were spurred on by some unnamed influence of the environment. In the Qur’ân, snakes are positive in at least one thing — that, with divine aid, Moses (as in Exodus 4.2) turned a staff of wood into one (Q 7.107 and 26.32).

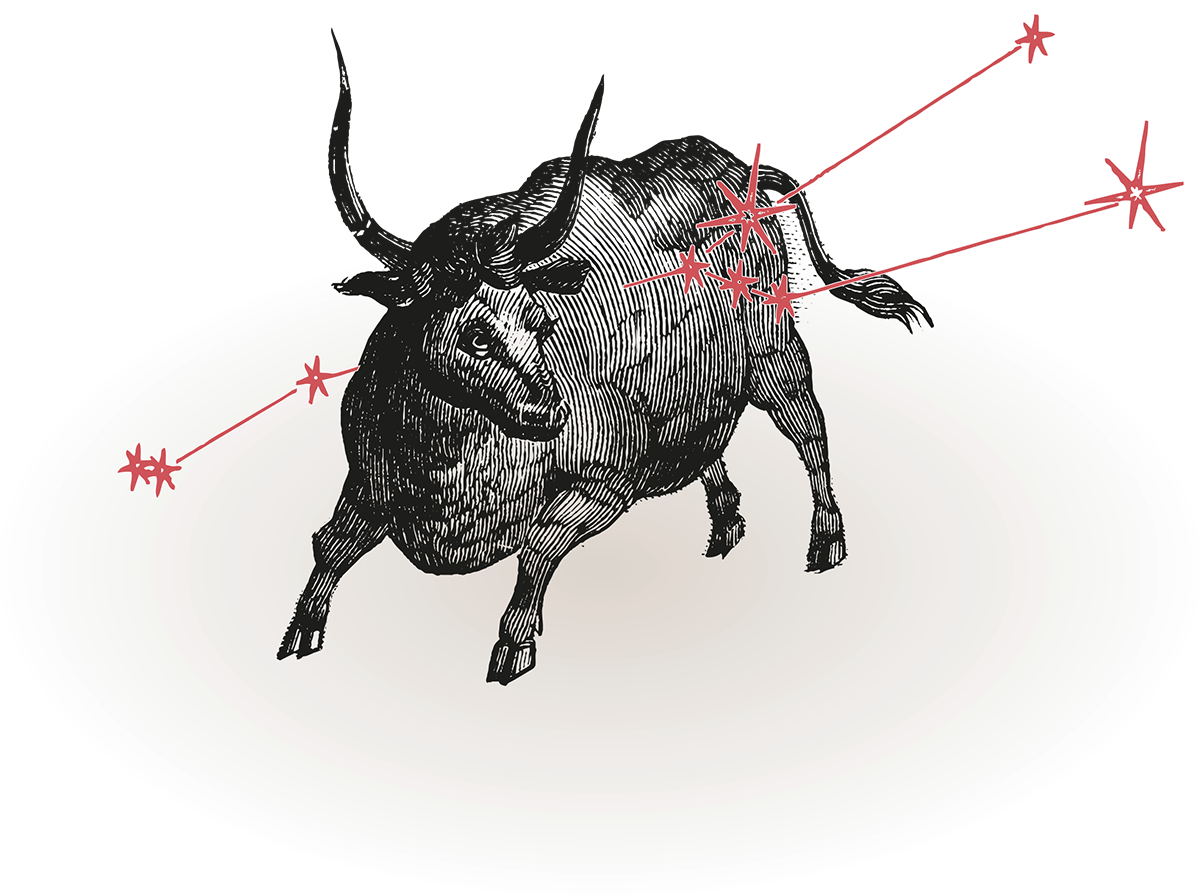

The constellation we know as Taurus is in Arabic Thawr, the Arabic word for bull. The similarity of sounds, taurus and thawr, may attest to a common root, or perhaps a loan word coming from one direction or the other. The animal is not rare in folklore. Not rare at all.

A census of animals in the mythologies of the ancient world may elicit the question, what is it about bulls anyway? Roberto Calasso’s The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony (1988), his update of Ovid's Metamorphoses, retells the Greek myths with an eye to contemporary themes, and you can’t help but notice how many bulls wander in and out of the Greek foundational stories. The palace of Knossos in Crete is famous for the mural which shows an acrobat on the back of a bull. Then there is the Minotaur, half bull; there is the Minotaur’s father, all bull; there is Io; then there is the bull which is believed to have been sacrificed in the Eleusinian mysteries. And they are still with us. We have, after all, a continent (Europe) named after a mythological figure (Europa) who wandered across the land mass on the back of a bull, the bull being Zeus in disguise. One of the initial puzzle pieces in Martin Bernal's attempt to reconstruct Mediterranean pre-history in Black Athena (vol. 2 1991) is to connect the bull cults of Crete with those of Egypt as related phenomena. In Zoroastrian tradition the creation of the first man was echoed by the creation of the first bull. After a while you might start to think that the culture of the ancient world was a franchise with only one logo, and this includes the lands we now call the Middle East. An earlier study with a big historical picture, Giorgio de Santillana’s Hamlet’s Mill (1967), discovers an astronomical logic centering around a bull. His argument has the elegance of a mythological vision which coincides mysteriously with science.

The scientific part was a prehistoric interpretation of things going on in the sky. It was the decision to locate the beginning of spring at the moment when the sun, in its annual circling of the ecliptic, crossed the celestial equator. (We call it the equinox. The sun crosses the celestial equator twice, once to mark the beginning of autumn, and once to mark the beginning of spring.) When that decision was made, the argument runs, plausibly enough, the point where the two circles intersect in spring was located in the constellation Taurus. In other words, spring came and the celestial year began with a bull, the ox of the Phoenician alphabet.

In De Santillana’s argument the bull, gradually, loses its primacy. The year began with Taurus, but as time went by the phenomenon called the procession of the equinox shifted the relation of earth to sky (we’re speaking in large units of time here), and the equinox edged over the border of Taurus into the realm of Aries. The bull was now the second sign of the Zodiac. This does not tell us why that particular arrangement of stars came to be called a bull (it doesn’t look like one), but, once we just accept the identification, De Santillana’s suggestion could explain numerous narratives in which oversize bulls are deposed from positions of authority, like the killing of the bull of heaven by Enkidu in the story of Gilgamesh.

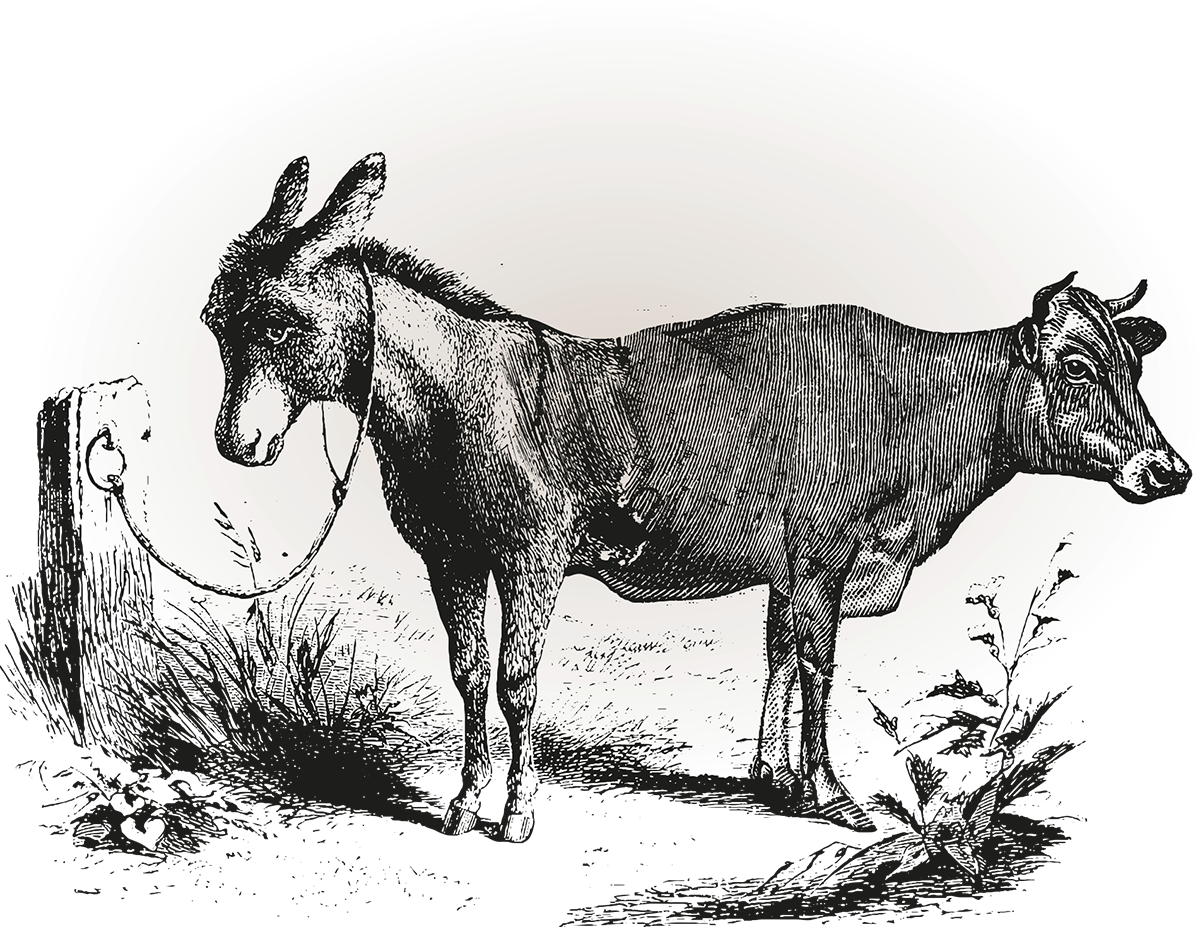

A thawr figures prominently at the outset of the Thousand and One Nights, even before the numbered nights begin, in the very first embedded tale, told not by Shahrazad but told to her, by her father the vazîr (English vizier). When Shahrazad offers to marry king Shahrayar her father is skeptical. After all, Shahrayar has been executing each wife the morning after her wedding night, so we might expect to hear a father at his most persuasive. Shahrayar as a husband would be many steps worse than that high school dropout with the tattoo. The looming threat to Shahrazad, however, becomes a matter for an intellectual debate. In the vizier’s story a donkey and a thawr are living on a farm owned by a wealthy merchant who for some reason knows the language of the animals. (Don’t ask why.) The thawr complains to his stable-mate, the donkey, how hard the work is when you are hooked up to a yoke plowing all day. The donkey’s advice is to pretend being sick, because the farmer won’t put a sick animal to work. The thawr follows the donkey’s advice and pretends to be sick, with the foreseeable result that the farmer yokes up the donkey to do the same work. We gather that the donkey is less fit for plowing, and ends up even more exhausted than the thawr. What began as a conflict between labor and management becomes a conflict between two of the employees.

I’ve never felt I understood why this story would persuade Shahrazad to abandon her marriage plans, unless her father expects her to hear it as a parable about the danger of unintended consequences. The news circulates around the barnyard that if the thawr doesn’t start working again the farmer will sell him to the butcher. (I’ve always assumed the donkey started the rumor, but nothing in any of the versions I have read says this explicitly.) So the next time the owner, with his wife, enters the stall the thawr breaks wind as a sign of health and, in Richard Burton’s 1885 translation, “frisked about so lustily that the merchant laughed a loud laugh and kept laughing till he fell on his back” (20).

After this, there is a sequel, a second story probably more relevant to Shahrazad: the merchant’s wife asks him why he laughed, at which point we are reminded that the merchant knows the language of the animals with an unmotivated, off the wall condition that he can’t tell anyone about his skill, on pain of death. So when the merchant decides to ignore the prohibition and tell his wife what has happened (evidently people love to tell secrets in spite of anything) this means he must prepare for his own death. But before this can happen he overhears the rooster, with his fifty wives, saying to the farmyard dog that the farmer should keep his silence and beat his wife instead. The message of the vizier’s story is, thus, silence: i.e. to let the prohibition stand which forbids us from telling our story. If speech is what will keep Shahrazad alive, this parable conveys the opposite message. Fortunately, you and I already know the story. If Shahrazad had agreed with the rooster’s advice (to remain silent), she would have followed the example of the farmer (who refuses to tell his wife). She disagrees with the rooster’s advice, no doubt recognizing it as a critique of her own strategy, the strategy she will use over the course of two and a half years-worth of stories).

If we consider the entirety of the Nights, this first sample is not a high-profile story, but in Richard Burton’s translation it is the occasion for a useful footnote:

The Arab word is ‘Taur’ (Thaur, Saur); in old Persian ‘Tora’ and Lat. ‘Taurus,’ a venerable remnant of the days before the ‘Semitic’ and ‘Aryan’ families of speech had split into two distinct growths. ‘Taur’ ends in the Saxon ‘Steor’ and the English ‘Steer.’ (29)

Not only does Burton commit himself to the claim that Indo-European and Semitic languages are siblings, but he goes out of his way to do it early in the book.

Two

Tha is for ithnân, “two” (stem: Th- N - Y). In a form with a ma- prefix, it means something divided into two parts, like a rhymed couplet in poetry, the poetic form called mathnawî (accent on the -aw-). It is always a dilemma to transliterate this word for English speakers, since it is a characteristically Persian form, and the Persian pronunciation is almost unrecognizable as the same word: masnavî, with an accent on the -î. All long Persian poems are in the masnavi form, for logical reasons. Arabic is so rich in rhymes that monorhyme can last quite a long time, as long as the rhymes hold out. In Persian, as in Turkish or English, with fewer rhymes to work with, the logical solution is the couplet, which requires only two rhyming words per unit. In common language the term Masnavi, used alone, always refers to a particular poem, the Masnavi of that great spiritual master and prolific poet Rumi.

In one of its substantive forms ithnân becomes thanawî, a dualist, member of a sect we call Manicheans, who take the universe to have two equal forces pushing things in opposite directions. Al-thânî, “second,” doesn’t just mean “second,” but, more broadly, “the other,” something outside our frame of familiarity, potentially a source of conflict. There are a lot of binaries which can organize an argument: center versus periphery, sophisticated culture versus naïve one, homeland versus invader, clear vision versus illusion, two partners in a dialogue, two bulls butting heads.

There is a famous dispute which has become a cautionary tale for students of the Middle East. The occasion was Edward Said’s commentary on an article by the historian Bernard Lewis, “Islamic Concepts of Revolution.” Lewis’s topic is the word thawra, “revolution.”

The root th-w-r in classical Arabic meant to rise up (e.g. of a camel), to be stirred or excited, and hence, especially in Maghribi usage, to rebel. It is often used in the context of establishing a petty, independent sovereignty; thus, for example, the so-called party kings who ruled in eleventh century Spain after the break-up of the Caliphate of Cordova are called thuwwar (sing. tha'ir). The noun thawra at first means excitement, as in the phrase, cited in the Sihah, a standard medieval Arabic dictionary, intazir hatta taskun hadhihi 'lthawra, wait till this excitement dies down — a very apt recommendation. The verb is used by al-Iji, in the form of thawaran or itharat fitna, stirring up sedition, as one of the dangers which should discourage a man from practising the duty of resistance to bad government. Thawra is the term used by Arabic writers in the nineteenth century for the French Revolution, and by their successors for the approved revolutions, domestic and foreign, of our own time. (Cited in Orientalism, 314-15)

Lewis demonstrates the specialist style in all its authority — the ability to launch philological flights from one realm to another and from one scale to another. And yet proofs by philology are always suspect. Readers of Edward Said’s Orientalism may recall that Lewis’s philology was a classic case of the western expert refusing to take Arab history seriously. Said’s comment is chastening. It could apply to a lot of us: “At no point in the essay is one sure where all these terms are supposed to be taking place except somewhere in the history of words” (314).

The entire passage is full of condescension and bad faith. Why introduce the idea of a camel rising as an etymological root for modern Arab revolution except as a clever way of discrediting the modern? Lewis’s reason is patently to bring down revolution from its contemporary valuation to nothing more noble (or beautiful) than a camel about to raise itself from the ground. Revolution is excitement, sedition, setting up a petty sovereignty — nothing more. (315)

This confrontation is a formidable and influential political conflict, but it’s also a meeting between two different modes of proof, or a thesis being stalked by its antithesis. Both claim actual evidence, and this makes it something more like a real debate. If Lewis’s argument is a Seurat pointilliste landscape, Said takes us close up to show the missing spaces.

Lewis’s argument moves from one Arab commentator to another, collecting words for change of government which might be translated as “revolution.” (If the words for revolution are static and cyclical at the verbal level, it seems to say, let’s just assume that deeds follow the etymologies.) His first choice is dawla: “The basic meaning of the root d-w-l, which also occurs in other Semitic languages, is to turn or to alternate — as for example in the Qur’anic verses ‘These [happy and unhappy] days, we cause them to alternate (nudawiluha) among men’ (Qur’an III, 134/140)…” (Lewis, “Islamic Concepts of Revolution,” 30). The thrust of his essay is to sketch a characteristic quietist attitude towards misrule in which change of governments is, etymologically, repetitive and arbitrary. “The Western doctrine of the right to resist bad government,” he adds, “is alien to Islamic thought” (33). It assumes, as a European norm, that revolution is standard equipment, a button on the western dashboard, a political ejection seat on all standard European models of government.

The comparison has a logical flaw. We can educe as many oppositional or revolutionary movements in one culture as in the other. The use of D-W-L as evidence of a static culture would be a stronger argument if the western term “revolution,” from volvere, to roll over, did not have an etymology just like its Arabic counterpart, D-W-L.

Lonely Bull

Kalîla wa Dimna is composed of a series of framing tales. The first is a sad, long narrative, the saddest character being a thawr, which pairs one character with another in an extended dialogue.

The story is widely distributed. A Sanskrit version is particularly old. And then it moves west. The plots remain more or less the same. The languages differ, along with the style. The translator into Arabic, Ibn al-Muqaffa‘, was a Persian intellectual who rose to a position of influence in the early days of the Abbâsid caliphate as a translator from Greek and Middle Persian, a writer of refinement, one of the men of letters who set the mold for Arabic prose style. Some of his spoken witticisms remain (he would greet a courtier with a prominent nose, one Sufyân ibn Mu’âwiya al-Muhallabî, saying “How are the two of you?” —Arberry 73), but, beyond anecdotes, Kalîla wa Dimna is his one extant complete work. This means that all we can see of his role in the history of Arabic prose is a collection of stories about hierarchy and power, rooted in pre-Islamic Iran and further east in India. They would have been enough to establish his reputation if he had written nothing else. E.G. Browne, judicious in so many things, regrets that Kalîla wa Dimna was the only surviving text (Literary History 1.76), but it is hard to agree with him.

The source Ibn al-Muqaffa’ used was a sixth-century Middle Persian text, now lost, which traces back to more than one text in Sanskrit, notably the (extant) Panchatantra, the five tantras. (You can hear the similarity between Persian panj, “five,” and Sanskrit “Pancha.” Or for that matter, the penta of Pentateuch, Greek for the five scrolls, i.e. Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.) There are a lot of translations whose origin is the Panchatantra. Its progeny is everywhere. (It reached English literature in 1570 in a translation, from Italian, by Sir Thomas North.)

The premise of moral parables is that they contain truths which are universal and unchanging, thâbit. The will to express them as profound truths is a constant, but parables and proverbs also contradict one another (many hands make light work but too many cooks spoil the broth). The term for moral parables in Arabic is a derivation of the verb mathala (M-Th-L), to resemble, to compare. A noun form, mathal (plural imthâl) means a likeness, example, parable or proverb, the constituent material of Kalîla wa Dimna. In Kalîla wa Dimna, as in the 1001 Nights, the stories are told to a king, Dabshalîm of India, by the philosopher Baydabâ (Bidpa, Arabic Baydbâ). Unlike the Nights, there is no threat to the storyteller. Dabshalîm just asks for stories (there are five requests), ordering up a particular moral, and Bidpa answers, not with the businesslike forward motion of the Nights, but with a series of leisurely meanders from one story to the next. Dabshalîm’s first request, which gives the book its title, is for a story in which two friends have a disastrous falling out because of calumny and treachery.

Bidpa’s long, wandering answer, is patched together with little ingenious stories ranged in debate formation, one answering the other. It starts slowly. First we hear a father’s advice to his oldest son (we hear it at tiresome length), encouraging him to seek his fortune. The son yokes up two oxen (thawrân), the narrator names them (Bandaba and Shatraba), Shatraba gets stuck in the mud, and the humans leave him behind. Once abandoned, or liberated, we forget the humans and Shatraba becomes the hero of the tale. Shatraba is the bull whose story will be sad, but we see him up close for the first time alone, against the backdrop of the natural scene. In A.J. Arberry’s translation:

Presently he came to a broad meadow adorned with all manner of succulent grasses and aromatic herbs, such as the Garden of Eden itself would have bit the finger of envy to behold, and Paradise looked on with eyes wide open, in amazed stupefaction. Shatraba approached it heartily and stayed there for quite a while…. It was not long before he became fat and prosperous. (76)

Shatraba’s bellows of pleasure waft across to a nearby animal community, and there we are introduced to their king (a lion) and two jackals, the title characters. Once we have met Kalila and Dimna, all the threads are in place on which the fables will be hung. They argue with one mathal after another.

Dimna is the heavy, the Machiavellian manipulator who notices the lion’s fear at the sound of the bull’s voice. If Dimna himself embodies a moral, it’s a pretty simple one: some characters are just no good. Dimna wants to gain power by using the king’s fear against him, so after an exchange of tales with Kalila, debating where his scheme is worth doing, Dimna goes to interview the ox himself and ends up introducing him to the lion. Lion and ox become friends, Dimna manages to establish discord between them. The result will be combat. (A disastrous falling out was, remember, king Dabshalîm’s assignment). Perhaps the moral is that, when you tell a story, you should tell the one your ruler wants to hear.

The sad turning point of the story takes place when the friendship of the lion and the ox, which would have been logical as the end of the story, is broken. Dimna argues to the lion that someone so strong as the thawr is dangerous just for his strength, so the only proper response is a pre-emptive strike. The lion kills the ox (another not illogical place to end the story) but he regrets it — and in a kind of epilogue Dimna is put in wathâqa, shackles, and thrown in prison (apparently animals have chains and a prison) where he dies of hunger. It satisfies our desire for justice, but not our taste for closure. There is never really a climax to the story, even if a bull gets sacrificed. In fact we never actually see the battle between lion and ox; it takes place offstage.

And Then

The Tha word thumma, roughly “and then,” is ubiquitous in narrative. Kalîla wa Dimna is seasoned with it at almost every line, “and then… and then…” It’s a prose rhythm that can suggest just one damn thing after another, like the fabric of history, before we have added a mechanism of cause and effect. It’s not rare to hear that paratactic narratives, the ones which take the connections for granted and leave them unstated, are naïve and simple, an early style of story-telling waiting to be outgrown. You sometimes hear the same thing about lyric poetry in Persian, the ghazal, that the connections between one verse and the next are arbitrary, that Persian esthetics produces not so much a unified poem as a collection of disconnected parts. William Jones, in his 1772 “Translations from the Asiatick Languages,” famously called them “orient pearls at random strung.” You often hear readers of Persian poetry prove that those poems do in fact have unifying elements — usually by the discovery of repeated images or moral themes. It doesn’t seem to matter much, but if the argument lasts long enough we might come up with a convincing definition of “unity.” It is not our problem.

The stem Th-Q-B is to pierce, to bore, to drill a hole. Threading a pearl is an image of accomplishing a difficult task. As an active participle it is thâqib: a word applied to an unnamed star, in a mysterious sura of the Qur’ân (86.1-4). Al-najm al-thâqib, the star which pierces.

Tha is also for thamâna, the number eight. Inside the constellation Thawra is the faint cluster of eight little stars, eight at least to the sharp sighted. For most observers it is seven. In Persian its name is Parvin. In Arabic it is Thurayya. You find it in English as the name Soraya. Thurayyâ is a beautiful fuzzy object, not particularly bright or piercing, though a name for it in India is The Razor.

The stem of the name thurayyâ seems to be tharan, earth or soil, giving rise to the proverb

این الثری من الثریا

Aina al-tharan min al-Thurayyâ

What has the earth to do with the Pleiades?

—which suggests that similarities of sound are an undependable index of meaning, or perhaps that common etymologies not infrequently contain opposites. A proverb arguing against proof by etymology.

One of the most famous poems of Hafez, the one addressed to the pale woman from Shiraz, concludes with a vision of the Pleiades. It is standard for a poet in the last bayt of a ghazal to stand away from the poem and speak in the second person as if in dialogue with a mirror. Hafez congratulates himself for having accomplished a great poem:

غزل گفتی و در سفتی بیا و خوش بخوان حافظ

که بر نظم تو افشاند فلک عقد ثریا راGhazal gofti-o dorr softi; biyâ wa khowsh bekhân Hâfez;

Ke bar nazm-e tow efshânad falak ‘eqd-e Sorayyâ-râ[“You’ve spoken a ghazal, you’ve threaded pearls (softan is the Persian equivalent of Arabic thaqaba); come here / go ahead and sing it beautifully, Hafez, so beautifully that over your verse the heavens (falak) will scatter the necklace of Soraya.” In Dick Davis’s translation:

Hafez, your poem’s written now,

The pearl you’ve pierced is poetry’s;

Sing sweetly – heaven grants your verse

The necklace of the Pleiades.]

It is a famous poem, famous among English fans of Hafez as a touchstone. This verse was the occasion William Jones, in his translation, used to exemplify his claim of randomness, as if to make Hafez say “yes, my verses are what you say they are, an unordered sequence”:

Go boldly forth, my simple lay,

Whose accents flow with artless ease,

Like orient pearls at random strung…

It’s a loose translation, and the Pleiades are absent from it, but there is something beautiful in watching Jones reconfigure the poem to make his own point. In Persian, the balance between pearls and Pleiades is complicated: Hafez praises himself for having pierced pearls and strung them together for a necklace. His reward is to have the sky offer him the Pleiades, or rather to “scatter” them (afshânad). The Pleiades are a necklace, ‘aqd-e Surayyâ (Thurayyâ). I don’t know a great deal about Hafez, but I can attest that the conclusion is beautiful: Hafez strings the pearls together and the sky sends them back disconnected, in the form of stars. So in the two metaphors for esthetic success, one comes from the crafts — piercing a hole in the round surface of a pearl; this is the work accomplished. The other comes from the sky, bringing Thurayyâ to earth as a reward. One is an act of putting a necklace together, the other an act of taking one apart.